Think of yourself as the best coaching tool there is. Tools need to be oiled, sharpened, repaired and protected to keep them in tip-top condition. So how do you stop yourself from becoming blunt, rusty and unfit for purpose?

In my experience, the most robust way to stay sharp is to be observed and given structured feedback related to our competence by someone who knows what great looks and sounds like. That’s mentor coaching. It is quite distinct from supervision, though you might classify mentor coaching as a form of supervision, as it focuses on one of the three functions of supervision (Hawkins and Smith, 2013), the developmental aspect.

Supervision is self-reported, whereby the coach talks about what happened in the coaching room. Mentor coaching examines the coaching right there in that room, either live or recorded. In mentor coaching, there is no hiding, nothing is (in)advertently left out. I’m not arguing for mentor coaching over supervision, though—both are crucial. Mentor coaching keeps us sharp. Supervision keeps us safe and sane.

Currently, ICF is the only coaching body that requires us to work with a mentor coach before we can become credentialed. That says to me that ICF really cares about how we show up in the room. Coaching is a practical profession that relies on us to practice at our edge.

“Our edge is the place where we are stretching ourselves, the point of our maximum ability. We need to stretch out of our comfort zone, out of our habitual behavior, and perch just the right side of a precipice, at its edge—our edge. Challenging ourselves in order to challenge our clients. Mentor coaching takes us to that edge, to our absolute best coaching self,” as stated in Mentor Coaching: A Practical Guide.

You can see then that mentor coaching is not just for those coaches seeking a credential: It is for lifelong professional development for every coach, at every level of the profession.

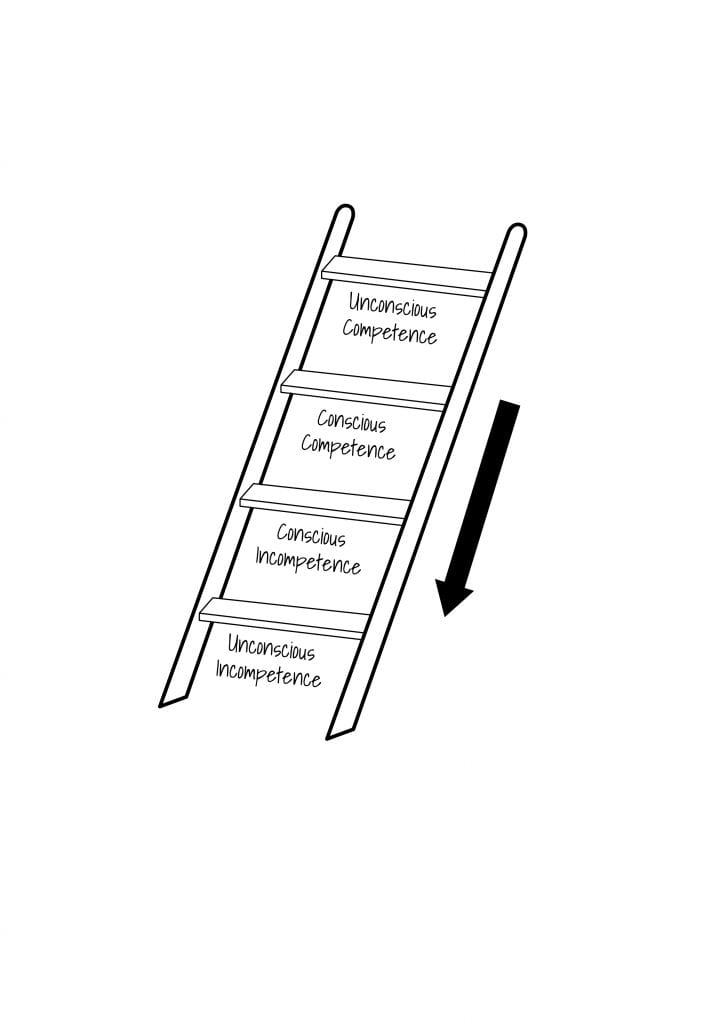

Mentor coaching is about regularly bringing ourselves back to conscious competence (Broadwell, 1969). We might aspire to unconscious competence, as that equates to mastery. But if we believe that as masters, we have nothing left to learn and therefore we don’t shine a light on our blind spots, deaf spots and dumb spots (Eckstein, 1969), we may well slip all the way down the competence ladder to unconscious incompetence.

Blind spots are the things we cannot see in ourselves, or perhaps we choose not to see them. Deaf spots are the things we don’t hear ourselves or our clients saying. Dumb spots are the things we don’t share out loud, whether that is our intuition, a challenge or direct feedback to the client. Research (Bachkirova, 2015) shows that coaches are self-deceptive when it comes to reflecting alone. We need to work with a reflective practitioner to make the blind spots visible, the deaf spots audible and the dumb spots noticeable.

You might think that feedback from our clients is enough. They are assessing whether they have resolved seemingly impenetrable problems or whether their life feels better now than it did before or whether they are closer to knowing who they really are. That’s all great feedback. But that doesn’t mean that you are at your edge. Only being observed by someone who knows what great looks and sounds like will give you the feedback that will enable you to sharpen that edge even more.

You might choose one-to-one mentor coaching, where you listen with your mentor coach to recordings of your coaching over time, and jointly assess them with the competencies in mind.

You might choose group mentor coaching, where members of the group take it in turns to coach one other person in the group, with the rest of the group observing along with the mentor coach. Everyone in the group gets to learn from everyone else’s coaching as well as from their own practice round.

Or, you can choose a combination of the two. For ICF Credentialing purposes, three of your 10 hours must be one to one. I’ll say it again, mentor coaching is for life, not just for credentialing. I propose that we each invest in three to four hours of mentor coaching per year, every year that we continue to coach.

I know what you are thinking: another expense. But think of it this way: How can we expect others to invest in coaching if we do not invest in our own development? Plus, we know from research (Olivero et al, 1997) that courses alone lead to only a 20% change in behavior and that percentage increases to 88% if we include individualized reflective practice, such as coaching, supervision or mentor coaching. Let’s take some of our own medicine so that we know we are doing our absolute best for our clients and for our profession.

Sources:

Broadwell, M.M. (1969) Teaching for learning, The Gospel Guardian, 20 (41): 1–3.

Eckstein, R. (1969) Concerning the teaching and learning of psychoanalysis, Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 17 (2): 312–332.

Hawkins, P. and Smith, N. (2013) Coaching, Mentoring and Organisational Consultancy, Supervision and Development, 2nd edition, Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Norman, C.E. (2020) Mentor Coaching: A Practical Guide, Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Olivero, G., Bane, D. and Kopelman, R. (1997) Executive coaching as a transfer of training tool: Effects on productivity in a public agency, Public Personnel Management, 26 (4): 461–469.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in guest posts featured on this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and views of the International Coach Federation (ICF). The publication of a guest post on the ICF Blog does not equate to an ICF endorsement or guarantee of the products or services provided by the author.

Additionally, for the purpose of full disclosure and as a disclaimer of liability, this content was possibly generated using the assistance of an AI program. Its contents, either in whole or in part, have been reviewed and revised by a human. Nevertheless, the reader/user is responsible for verifying the information presented and should not rely upon this article or post as providing any specific professional advice or counsel. Its contents are provided “as is,” and ICF makes no representations or warranties as to its accuracy or completeness and to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law specifically disclaims any and all liability for any damages or injuries resulting from use of or reliance thereupon.

Authors

Post Type

Blog

Audience Type

Coach Educators, Experienced Coaches, External Coaches, ICF Chapter Leaders, Internal Coaches, New Coaches, Professional Coaches, Team and Group Coaches

Topic

Coaching Toolbox, Discover - Your Coaching Career

Related Posts

The Power of Active Listening in Meaningful Coaching: Why Active Listening is the Most Essential Coaching Competency

Of all the foundational coaching competencies identified by the International Coaching Federation…

Allyship in Action: Coaching as a Catalyst for Change

Allyship is often framed as a value or an intention. In practice,…

Grace Under Fire: Building Stress Resilience for Coaches and High Achievers

There’s a unique kind of pressure that lives at the intersection of…